On the 'Criminalization of Politics'

Trump's indictments target a form of politics that no previous president had practiced—his bid for an authoritarian revolution

On Monday night in Atlanta, the national press assembled to witness the occasion of Donald Trump’s fifth1 indictment to date. The charges that arrived in a 98-page indictment around 11 p.m. were the most sweeping yet, charging Trump and 18 of his allies with a vast conspiracy to overturn the 2020 presidential election in Georgia.

The centrality of the Trump’s political career to the criminal jeopardy he finds himself in has, naturally enough, led some of his allies to decry the “criminalization of politics.” We can expect those complaints to grow as the judicial proceedings continue and the 2024 presidential campaign begins in earnest. And simple though it may be, I think it’s worth reckoning with the subject head on.

Each of Trump’s indictments is concerned with his pursuit of political office and his unwillingness to yield it. The first indictment he faces, brought by the Manhattan DA’s office in New York state court, concerns a fairly elaborate hush money scheme that Trump and his then-attorney Michael Cohen allegedly designed to keep word of Trump’s tryst with Stormy Daniels out of the press in the immediate run up to the 2016 election. The second and third indictments, brought by the special counsel’s office in federal court in Florida, relate to vast quantities of classified documents, a piece of the presidency that Trump—for reasons that are still not fully understood—brought home to Mar-a-Lago after his term concluded. The fourth indictment charges Trump in federal court in Washington, D.C. with conspiring to overturn the 2020 election result by illegal means. And as already mentioned, the fifth indictment expands on that theme.

The three indictments Trump faces in the hush money prosecution in New York and the classified documents case in Florida are fundamentally about venal matters—cooking the books of a business and stealing government property—that only reach the realm of political controversy because Trump’s political persona is attached to them.

The other two indictments, in Washington, D.C. and Georgia, come closer to the heart of the matter. Trying to overturn the valid result of the 2020 election is a form of politics. Rather than politician’s the usual bread-and-butter of policymaking and electioneering, Trump’s gambit put the fundamental governing principle of the country at issue. It asked whether the loser of an election could disregard the result and remain in his office through deceit, stubbornness, chicanery, bullying, and—all else failing—street violence. In other words, it’s a type of politics that had not been practiced by any American president in 231 years—revolutionary politics.

The complaints about ‘the criminalization of politics’ proceed from a conception of ‘politics’ as a sandbox within our constitutional system where rival political factions are allowed to compete for the favor of the voters and wield the mandates conferred by those voters with few fixed rules.

American law has developed a hands off approach concordant with this view of politics. The political speech that precedes an election is considered to be the core of type of expression protected by the First Amendment. American courts’ theories of justiciability shield much of the behavior of politicians in office from judicial scrutiny.2 One of those theories of justiciability, the political question doctrine, holds that courts can’t review decisions that the Constitution commits to the political branches.

This conceptual framework makes sense for a huge variety of political questions that exist within our consitutional system: What bills should the House and Senate pass and send to the President? What will taxes be like next year? Will the government pay for people to have health insurance? Should the president be impeached? Will there be peace or war? How much power should the FEC have to regulate campaign finance? Should we propose a constitutional amendment to the states or call a constitutional convention? We have, in the Constitution, a set of previously agreed upon rules for working these questions out, more or less.

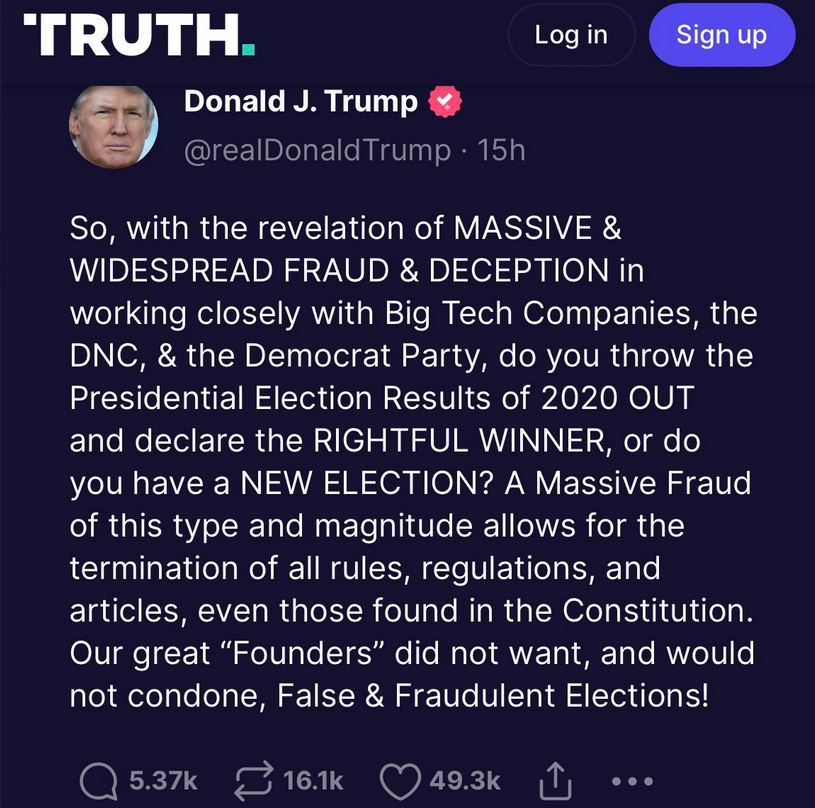

But obviously the political system we have established by consensus has its limits. Should Donald Trump be installed as dictator? Should he unilaterally cancel the next election? Should he unilaterally cancel the last election? Can Donald Trump seize upon an invented pretext to terminate “all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution”?

These questions, while theoretically political, are wholly anathema to our Constitution and our democratic society. To place them firmly outside the bounds of quotidian politics, we make every elected official swear an oath to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution. For believers in a living God, breaking that oath is a mortal sin. And for all Americans, conspiring to overthrow our Constitution has always been an exceptionally grave crime.

Five if you count the superseding indictment in the classified documents case in federal court in Florida separately from the initial indictment in that case, which imho you ought to do.

A formerly large exception of public corruption prosecutions has shrunk substantially after a series of lamentable Supreme Court decisions.