How do you solve a problem like Alito?

May 11, 2022

The first draft of an opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson, authored by Justice Samuel Alito and published by Politico last week, and confirmed as authentic by the Supreme Court, probably heralds a final decision next month that will permit states and territories to lawfully ban and criminalize obtaining or performing an abortion before viability for the first time in 49 years.

If that decision comes, the New York Times wrote, “abortion may be banned or tightly restricted in as many as 28 states in the weeks and months ahead.” Through these restrictions, an old tool of patriarchal control of society, and particularly of anyone who has a uterus but lacks the means to travel, will once again1 be wielded by many states and territories.2 In the other 22 states and D.C., obtaining a pre-viability abortion is likely to remain legal for the time being, but it will no longer be a right protected by the federal constitution. It appears, in short, that young people in America will have fewer guaranteed rights in adulthood than their parents and grandparents enjoyed. The imminent reshaping of the legal protections for individual rights, and not just abortion rights, will affect everyone in America.

In the cycle of news that has accompanied the disclosure of Alito’s draft, attention has naturally devolved on easier subjects to talk about than the looming rescission of vital, guaranteed rights. Mainstream news spent nearly a whole week talking about the historic nature of the leak and watching conservatives fulminate about punishing the leaker and convince themselves, without evidence, that the leak must have come from the chambers of the three liberal Justices. Then, last weekend, we learned definitively from a Washington Post report that conservatives have been leaking the details of the private conferences3 where the Justices discuss their views on pending cases. Shortly after that revelation, the main wellspring of attention shifted to the nature of the protests against the pending decision that have cropped up outside some conservative Justices’ houses. Senator Susan Collins (R-ME) even called the police when she found sidewalk chalk outside her Bangor home. Today, Politico reported another leak—that Alito’s Dobbs draft hasn’t been superseded by any subsequent drafts or questioned by any draft dissents.

The large volume of process and protest coverage is inevitable, as the Supreme Court reels from serial breaches of its cherished omerta and American society reacts to a momentous development. However, kaleidoscopic coverage of the impact the draft is having on the Court and the American scene has tended to detract from analysis of the draft opinion and its author. I’d like to try to turn the spotlight back onto Justice Alito and what he wrote.

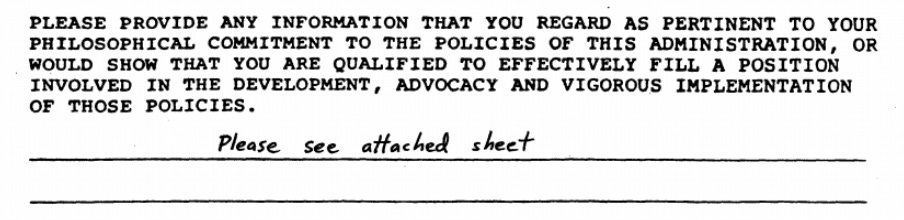

Back in 1985, before he got to be a Justice or even a Circuit Judge, Samuel Alito messed up. He told the truth exactly once, and he told it on paper. Having reached the fairly exalted civil service position of line attorney in the Reagan Solicitor General’s office, Alito applied for a promotion. He wanted a political position, Assistant Attorney General, which requires a presidential appointment, and Reagan’s appointments office had some questions about the young man’s devotion to Reaganism. This was the key prompt put to Alito:

On a typewritten addendum that would become the centerpiece of his Supreme Court confirmation twenty years later, Samuel Alito answered. I’ve put his full, highly revealing response at the end of this item, but here is the quote that set the world on fire (emphasis added):

Most recently, it has been an honor and source of personal satisfaction for me to serve in the office of the Solicitor General during President Reagan’s administration and to help advance legal positions in which I personally believe very strongly. I am particularly proud of my contributions in recent cases in which the government has argued that racial and ethnic quotas should not be allowed and that the Constitution does not protect a right to abortion.

One can imagine the widening eyes of the Senate Judiciary Committee staffer who first read that line in 2005. Alito had written in his college yearbook at Princeton in 1972 that he intended “eventually to warm a seat on the Supreme Court,” but this was a misstep along that path. It was a clear statement of a legal position on a case that might come before the Court seeking to overturn Roe v. Wade—the case, first and foremost, that the conservative movement had been plotting to undo since the ‘70s.

A long tradition holds that judges, even appeals judges on the highest court of the land, should decide the cases that come before them based on the record and the arguments and not by reference to the judge’s preconceived ideological position. In the Supreme Court building, this tradition is honored mostly in the breach, but it held real weight in the Judiciary Committee hearing room in 2005.

Predictably, Alito’s explosive statement in his DOJ application came up frequently at his confirmation hearing. Republicans and Democrats alike asked him if he had a view already inclining him to overrule Roe because, as he had said, “the Constitution does not protect a right to abortion.” Alito had, by my count, three thematic responses to these questions.

First, Alito said that if a case seeking overturn Roe came before him, “the first question” he would consider would be whether Roe ought to be upheld on the basis of stare decisis—the doctrine that “it is necessary for a court to follow earlier judicial decisions when the same points arise again in litigation.”4 The Supreme Court famously does not always follow its own earlier cases; its overrulings of earlier decisions are often the stuff of legend, the most famous probably being its decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) overruling Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). But Alito outlined a number of reasons why stare decisis might apply for Roe. He said Roe was an “important precedent,” it had been on the books a long time, and it had been challenged repeatedly and reaffirmed, both on the merits and, in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), on the basis of stare decisis. “When a decision is challenged and it is reaffirmed,” Alito said, “that strengthens its value as stare decisis.”

Second, Alito said that if he reached the merits of a case seeking to overturn Roe, he would approach the issue “with an open mind.”

Third, Alito said that the DOJ application was not a sincere expression of his beliefs, just telling the Reagan administration what it wanted to hear, and that also, as a judge, he had learned to bury his personal inclinations so deep that it didn’t affect his work. Alito said to Senator Feinstein:

First of all, it was different then. … I was an advocate seeking a job. It was a political job. And that was 1985. I’m now a judge, you know. I’ve been on the circuit court for 15 years. And it’s very different. I’m not an advocate. I don’t give heed to my personal views. What I do is interpret the law.

There were reasons to doubt the genuineness of these deflections in 2005. As you can see below, Alito’s assertions are in substantial tension with almost every sentence of Alito’s 1985 application. It expresses a sincere and permanent commitment to conservatism, a motivation dating back to his college days to change the law handed down by the Warren Court, a belief that liberal “usurpation” could and should be corrected by “judicial appointments, litigation, and public debate,” and Alito’s “personal satisfaction” when the legal work he does aligns with his own beliefs. In this latter regard, Alito said that arguing for Reagan that there’s no Constitutional protection for abortion (despite the law saying the contrary) made him “particularly proud.” These are the words of a fervent judicial activist, not someone who considers stare decisis first and foremost, approaches every case with an open mind, and divorces his personal convictions from his work.

Now, with the benefit of the leaked draft opinion, we can say definitively that Alito broke his word.

When the issue of Roe came before him, Alito did not consider stare decisis first, as he had promised to do. “We begin,” Alito wrote, “by considering the critical question whether the Constitution, properly understood, confers a right to obtain an abortion.” (This phrasing mirrors the language Senators found so concerning in his 1985 DOJ application.) Alito goes on to deliberately shunt the analysis of stare decisis to the end, and to criticize the Casey Court for not doing the same. “The controlling opinion in Casey reaffirmed Roe’s ‘central holding’ based solely on the application of stare decisis,” Alito writes, “but as we will explain, proper application of stare decisis required an assessment of the strength of the grounds on which Roe was based.” Under this remarkable reframing of the doctrine, stare decisis means no more than that the contemporary court will not overrule an earlier case so long as it still agrees with it. Alito does not return to the applicability of stare decisis until Section III of his draft.

And when Alito does return to the subject, his analysis of whether to adhere to stare decisis is unrecognizable. Alito makes no reference to the factors he listed in his confirmation hearing: the decision’s age and its record of reaffirmance. Instead, he lists five other factors favoring overruling—the nature of the Court’s error, the quality of its reasoning, the “workability” of the rules imposed on the country, the disruptive effect on other areas of the law, and the absence of concrete reliance.5 Nowhere does Alito discuss that Roe has been on the books for 49 years and Casey for 30 years, or that they have been repeatedly challenged and repeatedly reaffirmed, as factors that weigh in favor of stare decisis. To the contrary, Alito cites each decision’s age only to observe that it has failed, over all those years, to settle the question of reproductive rights in the people’s minds. (The continued political division over abortion, of course, is a signal achievement of the conservative movement that Alito is avowedly a part of.)

Alito’s shotgun approach to attacking Roe and Casey on the merits do not bespeak an open mind or the sangfroid of a disinterested judge. I’ll offer a few examples:

“Roe was egregiously wrong from the start,” Alito writes at one point, acid dripping from his pen. The dictum has no legal significance.

“Procuring an abortion is not a fundamental constitutional right because such a right has no basis in the Constitution’s text or in our Nation’s history,” Alito writes. The United States has been a Nation for only 246 years; Roe has been a part of that history for 49 of those years, 20% of the whole.6 But the experience of the two generations of Americans who have grown up with a guarantee of personal autonomy, counts for nothing in Alito’s analysis. Whatever roots have grown downwards for five decades, they still haven’t reached a depth that earns his respect.

Alito only gives half a bar to a theory advanced in amicus briefs by the United States and Constitutional Law Scholars that the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause “supplies an additional, independent basis for the constitutional right to an abortion.” Alito simply says that the Court’s earlier cases have decided that regulating abortion does not constitute invidious discrimination against women—coincidentally, it’s one case from the 1970s, Geduldig v. Aiello and one from the early 1990s, Bray v. Alexandria Women’s Health Clinic. However, Alito doesn’t for a moment weigh the assertion that there’s no gender discrimination in abortion regulation against common sense or the lived experience of women around the globe, and he certainly doesn’t apply any of the stare decisis factors he wields against Roe and Casey to Geduldig and Bray to see how they fare. That sort of analysis is reserved only for cases he’s got a preexisting vendetta against.

Alito is almost entirely silent on the procedural posture of the case. There’s not a word about the court’s jurisdiction or the parties’ standing in the entire draft, and more saliently not even a drop of ink is spilled explaining why it was okay in this case for Mississippi to demand that Roe and Casey be overturned only after Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death and Amy Coney Barrett’s rushed confirmation, when it had not raised that argument in its June 2020 cert petition. The Court generally does not consider arguments that are omitted from the cert petition. (An unjustly ignored amicus brief explores this issue eloquently.)

Ultimately, all the evidence suggests that Justice Alito is not the even-tempered judge he presented to the Senate in 2005. He’s not a person concerned with hearing and weighing all the arguments. He’s the fervent conservative activist who applied to Ronald Reagan’s DOJ and wrote the words set out below, and he always has been. Justice Alito told the truth seeking that DOJ position, and he lied to get the Supreme Court seat he now holds.

Here is Alito’s “attached sheet” to his 1985 DOJ application in its entirety (the full application is here):

Of course, it bears noting that some states have gotten ahead of the game since the Supreme Court has, tellingly, declined to enforce the right guaranteed by Roe and Casey since last September.

In the oft-ignored U.S. island territories, things are too complicated to make a blanket statement. Abortion is legal and available in the U.S. Virgin Islands and in Puerto Rico, which has had a long and fraught history with the procedure since its legislature repealed the laws against it in 1937. Puerto Rico was once, before Roe, a destination for travelers from the mainland United States seeking abortions, and it may again become one. In American Samoa and Guam, abortion is technically legal but already practically unavailable without traveling to another jurisdiction. In the Northern Mariana Islands, like several U.S. states, a criminal law banning abortion remains on the books in the CNMI, but it has been held in abeyance since a 1995 opinion from the commonwealth’s attorney general found that a right to abortion was one of the fundamental rights established by Supreme Court case law that the CNMI adopted when it entered the covenant to join United States in 1976. It seems likely that the old criminal law could spring back into effect there too if the Supreme Court’s final decision overrules Roe and Casey. Regardless of the legal status, throughout the Pacific, residents of American territories generally have to take a long flight to Hawaii to obtain an abortion.

Aficionados of the Court will know that these conferences are attended by the Justices alone, with the most junior Justice assigned to answer the phone if anyone calls.

Black’s Law Dictionary, Eighth Edition (2004).

The present conservative majority, somewhat hilariously, can never quite settle on the list of factors it wants to use to overrule an earlier case. Another major overruling recently, Janus v. State, County, and Municipal Employees, also listed five factors, but only three of them reappear in the same form in the Dobbs draft. From Janus, the Dobbs draft takes (i) quality of reasoning, (ii) workability, and (iii) reliance, but the draft opinion omits (iv) developments since the decision was handed down, replacing it with “the nature of the Court’s error,” and it reformulates (v) consistency with other decisions as the “disruptive effect on other areas of the law,” focusing its analysis on what it sees as Roe and Casey’s conflicts with “longstanding background rules.”

I can hear the reader shouting at me, at this point: We’ve been over this! But there are two separate questions at play in Alito’s opinion—whether stare decisis applies to Roe & Casey, saving them from being overruled, and whether the right to get an abortion is “deeply rooted” in our Nation’s history, which would (by Alito’s standards) make Roe & Casey correctly decided on the merits.