An Episode in the Outrageous Captivity of Britney Spears

July 10, 2021

Dear Readers,

With a little bit of chagrin and frustration at feeling ill-informed by the news coverage of the Britney Spears conservatorship over the years, I’ve been looking through the primary records at the probate court.

At 1,379 entries on the 13-year-long main docket—and more for her little-covered trust—it’s an intimidating volume of material, but it’s also strangely incomplete. The Court’s public records of the case start at the end of July 2008, but the conservatorship actually started in sealed proceedings six months earlier, on February 1, 2008—the temporary conservatorship was originally granted for only three days. One might reasonably assume that the records of these crucial early months are available to the parties, but just hidden under seal for the rest of us; however, that doesn’t always seem to be the case. Spears’ court-appointed lawyer, challenged by an accountant involved with the conservatorship to produce evidence of his fee allowance of up to $10,000 per week in order to be paid, couldn’t do it. “It appears that the court records don’t go back to March 2008,” he wrote haplessly. (Notwithstanding his difficulties, it is possible to find some of the early records attached to more recent documents.)

What follows is my first attempt to piece together a story from these primary documents, which I’ve posted publicly on DocumentCloud, including a full transcript of the recent hearing at which Spears spoke. The other public transcripts I’ve seen have only quoted from Spears’ main statement, but as I hope to show, there’s more in that hearing that’s interesting. Hope you find this helpful, and I hope you’ll subscribe because there’s more to come.

Britney Spears spoke clearly enough in open court to send reverberations around the world, but she still managed not to be heard by Judge Brenda Penny.

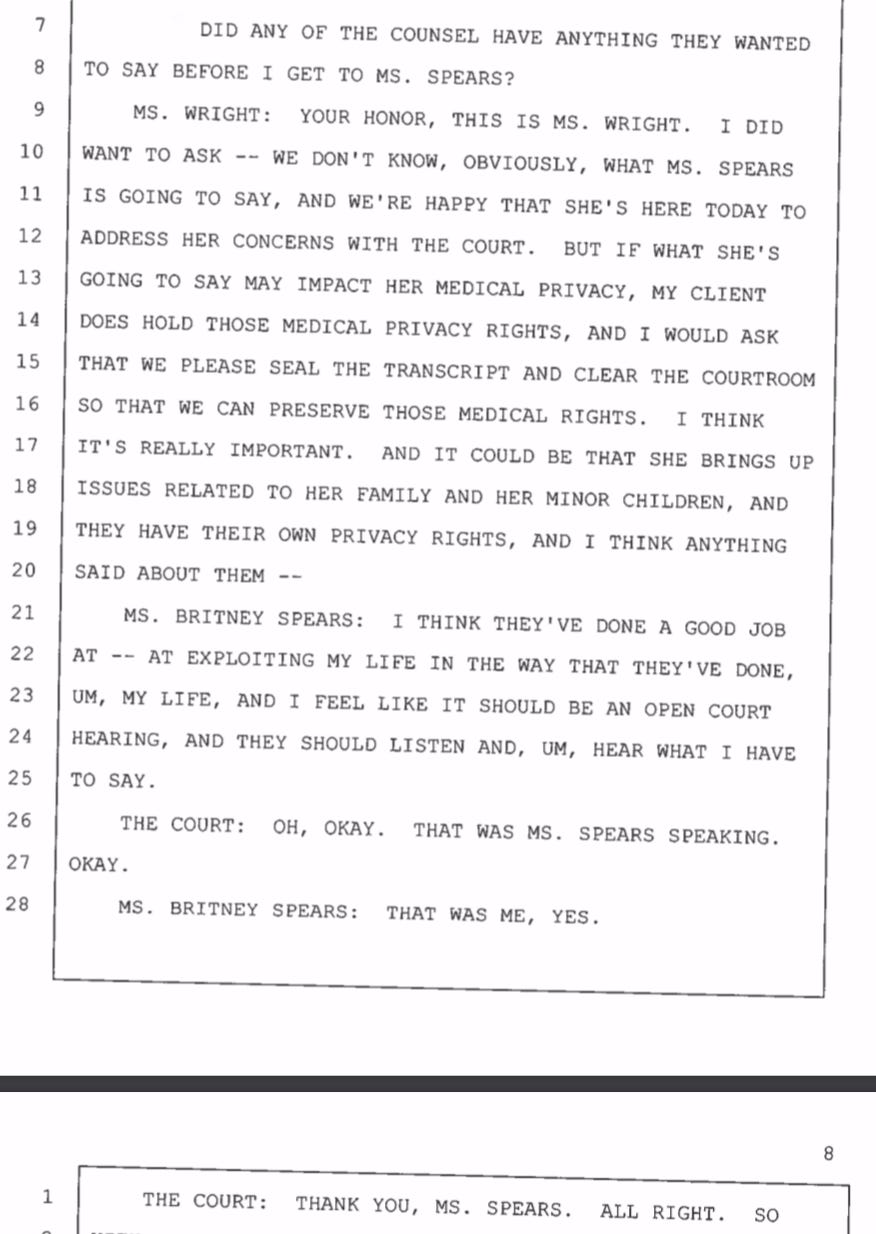

According to the official transcript1 of the June 23rd hearing, Spears said to the judge:

I’m not sure how you make your decisions, ma’am, but this is the only chance for me to talk to you for a while. I need your — your help. So if you can just kinda let me know where your head is. I don’t really honestly know what to say, but my requests are just to end the conservatorship without being evaluated. I want to petition basically to end the conservatorship, but I wanna — I want it to be — petition to end it, but I don’t want to be evaluated, to be sat down in a room with people four hours a day like they did [to] me before, and they made it even worse for me after that happened.

Three times in two sentences, Spears directly implored the judge to take action terminate the conservatorship that has held her in subjection since 2008. She invoked the judge’s “help,” she requested that the court “end the conservatorship,” and she repeatedly expressed a personal wish to “petition to end it.”

To another party to the proceeding, as well as the public,2 the meaning of these words was unmistakably clear. “As a result of the Conservatee’s testimony at the June 23, 2021 hearing,” a Managing Director of the Bessemer Trust Company said in a sworn declaration accompanying a petition to resign from the case a week later (see Exhibit B at the link), “I became aware that the Conservatee objects to the continuance of her Conservatorship and desires to terminate the Conservatorship.”

However, to Judge Penny and Spears’ own lawyer, Samuel D. Ingham III, the matter quickly became more clouded. Immediately after Spears’ statement, the transcript records the following conversation between the two of them:

THE COURT: So, you know, Mr. Ingham, you know that there are methods to get conservatorships terminated, and if that’s something that you’re looking at doing, you know you can certainly file a petition for the court to consider that.

MR. INGHAM: Your honor, it’s difficult for me to respond to that issue without breaching attorney/client privilege, and so therefore I won’t even try to touch that issue.

THE COURT: I know.

MR. INGHAM: I am concerned about several of the issues that my client has raised here. I think that the other family members and fiduciaries here will doubtless want to weigh in in some fashion. If my client directs me to file a petition to terminate, I’m happy to do that. So far, she has not done that. That’s the most that I will say about that issue.

THE COURT: I understand.

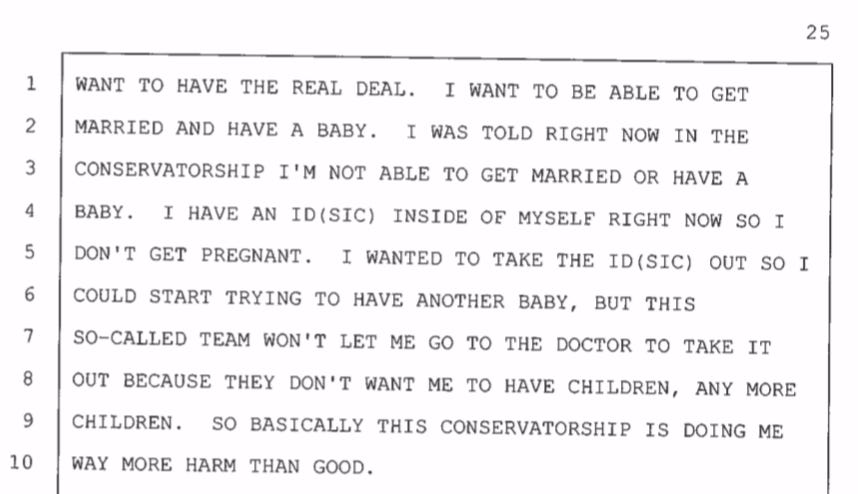

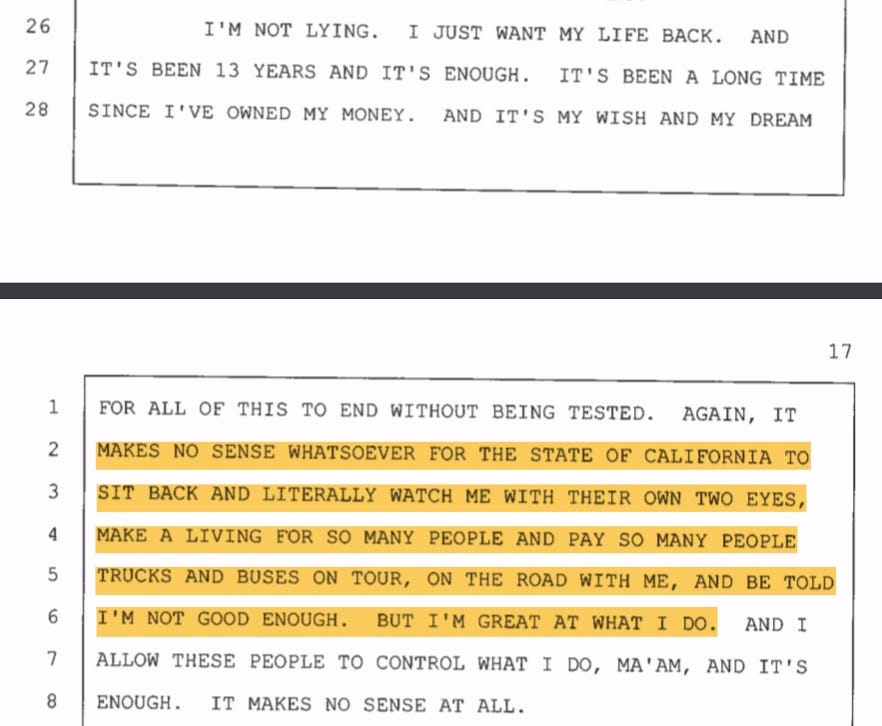

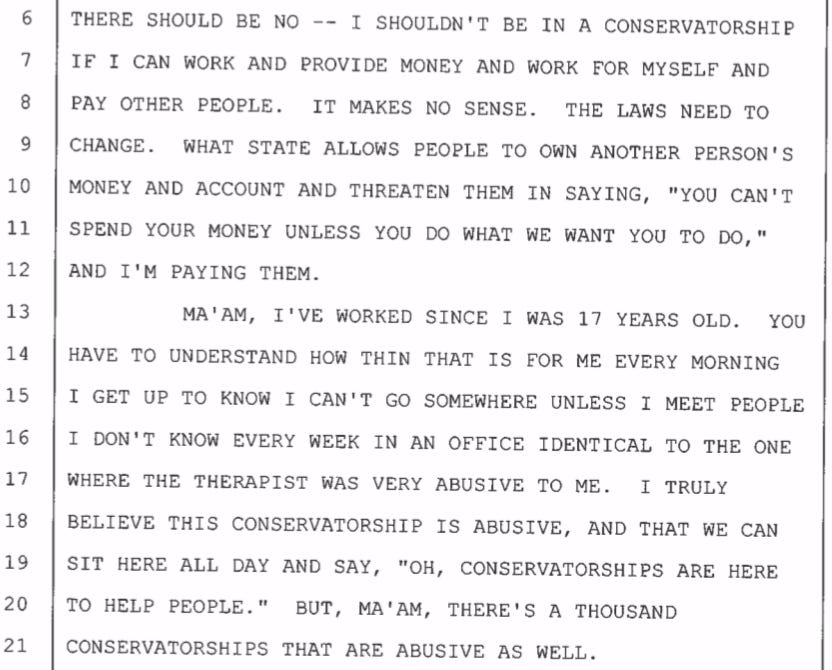

It’s hard to know where to start to convey how frustrating this is. In so many words, Spears herself had just orally petitioned3 the court to terminate her conservatorship—marshaling a compelling argument from her own personal experiences of abuse,4 the publicly observable evidence of her own competence to manager her own affairs,5 her amateur research into the precedents for terminating similar conservatorships (and anticipated objections to the termination),6 and the public policy concerns about conservatorship abuse.7 She did so in straightforward, earnest language and at length in a special personal appearance. From someone who’s not trained as a lawyer, it was a forceful presentation.

In addition, context strongly suggests that Spears engineered the hearing herself in order to go around her lawyer. Before Spears began to speak, Ingham said:

This indeed is a special status hearing that was set at the request of my client. As I understand it, the only item on the agenda, apart from whatever questions the court would like to ask, is the opportunity for my client to address the court. […]

My client is free to discuss any aspect of the conservatorship that she wishes, and is welcome to say whatever she likes. For the record, I would like to state that I have not in any way attempted to control or filter or edit anything that she has to say today. These are entirely her words.

In her statement, Spears said she wasn’t aware of her own rights in the proceeding, casting doubt on the quality of Ingham’s representation, and made clear multiple times that she wished to hire her own lawyer.

Ma’am, I didn’t know that I could petition the conservatorship to end it. I’m sorry for my ignorance, but I honestly didn’t know that.”

[…]

“I haven’t really had the opportunity by my own self to actually handpick my own lawyer by myself, and I would like to be able to do that.”

In a presentation that Ingham said was “entirely her words,” Spears openly told the court she wanted her conservatorship to be terminated and wanted a petition filed to that effect, she told the court reasons why it was not necessary and should be terminated, she cited—after her own fashion—legal and policy justifications for her request, and she made a strong implicit case that she was receiving ineffective assistance from Ingham, her lawyer.

In her cogent and thorough address to the court, it seems to me, Spears eliminated most of our opportunities for temporizing. Even though we don’t know the secret diagnosis8 from thirteen years ago that led the court to strip her of the right to choose her own lawyer, it’s difficult to maintain she might not have known what she was saying on June 23rd. Her evidence that she has the desire and capacity to manage her own life can’t really be denied, and her story of abuse under the conservators is genuinely harrowing. The notion that she secretly embraces the conservatorship in privileged sessions with the court-appointed lawyer she wishes to fire is pretty laughable.

For Ingham to then get up, disregard her plainly expressed desires, allude vaguely to some purportedly privileged information that might contradict them, and say he needed separate instructions in order to gauge his client’s true intent was an insult to her efforts. For the judge to agree with him and make his inaction decisive9 without further inquiry into the circumstances, when the court and not Spears is responsible for Ingham’s service as her lawyer, is a betrayal of basic principles of justice.

Since the June 23rd hearing, Ingham has tendered his resignation, effective upon the appointment of “new court-appointed counsel”—once again disregarding his client’s wishes to pick his successor herself.

While he remains Spears’ lawyer for now, Ingham has not yet filed a petition to terminate the conservatorship as his client requested, and the court has not taken any action on its own.

The court reporter’s transcript of the June 23rd hearing was recently filed as an attachment to a petition by Jodi Montgomery, Spears’ Conservator of the Person for the last two years, that asks the Court to appoint a guardian ad litem—a special purpose representative—to help Spears select a new lawyer in the wake of Samuel D. Ingham III’s resignation along with co-counsel. I’ve made a public copy of this petition available on DocumentCloud; see Exhibit A at the link for the transcript—which is quoted extensively throughout this post.

Unfortunately for Spears, the California Probate Code appears to require that petitions be made in writing; that’s ordinarily something her lawyer would help her with.

An order of the court on February 6, 2008 (see Exhibit 1 at link) signed by Reva Goetz, the Judge Pro Tempore who previously oversaw the conservatorship, made this finding based on a declaration of a Dr. J. Edward Spar, but that declaration has never been unsealed or made public. The same declaration, according to Judge Goetz, said that Spears did not have the ability to attend a court hearing—a conclusion that seems to have been overtaken by events.

At the end of the hearing, Judge Penny said “you know, some of the issues that Ms. Spears raised this afternoon do require a proper petition to be before me for me to consider, whether it be the counsel or termination [….]” Accordingly, unless and until Ingham or his successors duly file a written petition for termination, the court’s position seems to be that no further action will be taken.