The Enduring Strangeness of the Manchin-Schumer Contract

A Close Reading - October 12, 2021

Dear Readers,

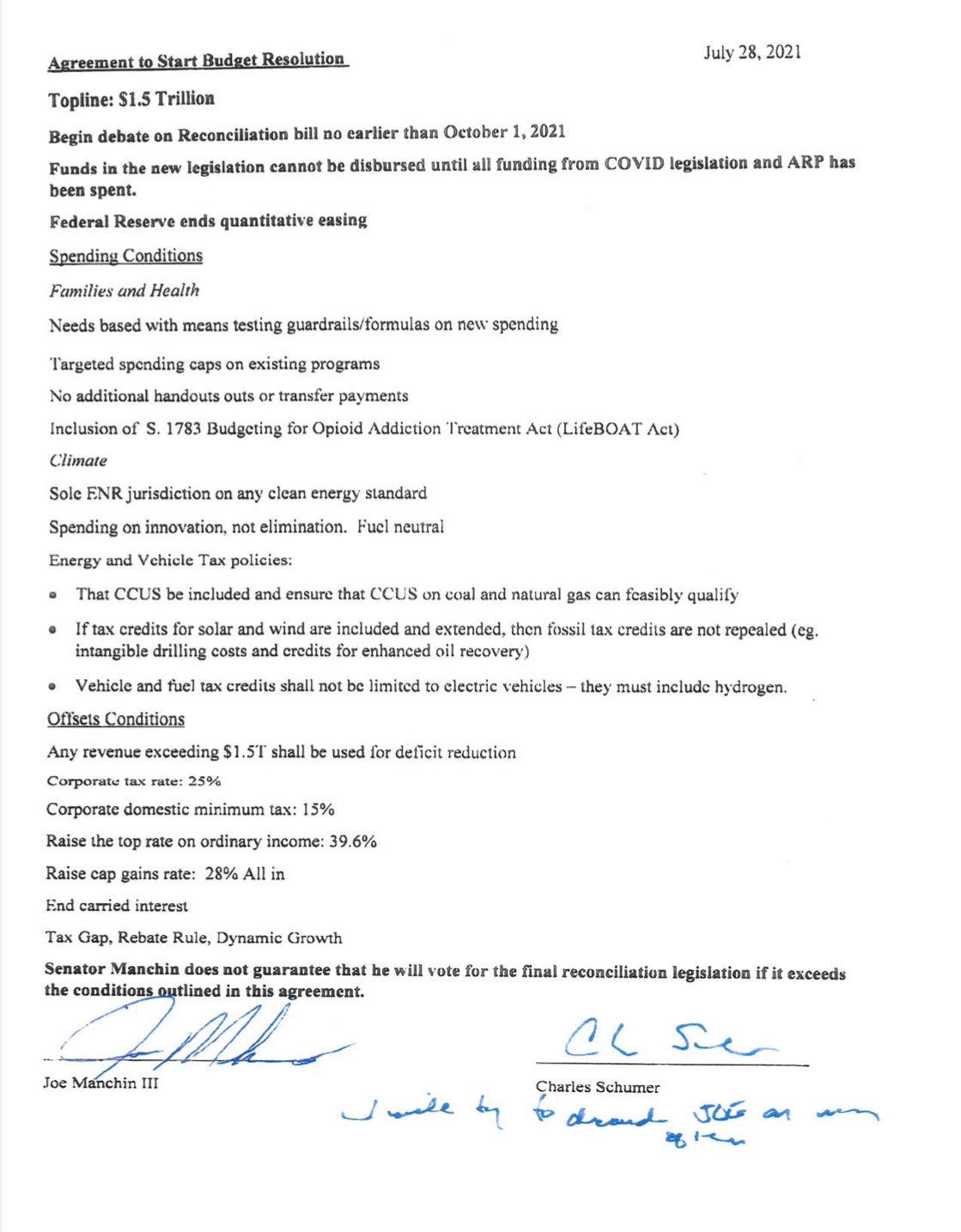

In late September, several months into the interminable legislative mulling of President Biden’s domestic drama, a curious document landed on Capitol Hill like a mortar. A single sheet, bearing a date in midsummer, it contains a terse recitation of terms for a potential reconciliation bill and is solemnized by the signatures in blue ink of Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer. It is distinctly different than anything that had been discussed before it emerged.

The questions that surround the simple existence of this document are as important as they are difficult to answer. We don’t know how it came to be. (Did Chuck Schumer and Joe Manchin find a dark corner and a couple of cold drinks one night and hammer out this approach? Did Manchin march into Schumer’s office and extract his signature as a condition of some other vote?) I fear, though, that they tend to distract us from the strangeness that’s printed on the page for all to see. That’s ultimately the most important fact of this document, which is now in many ways anchoring the debate over Biden’s agenda in Washington. And I mean to make it my subject here. I have written today about the four boldface items at the top today, and I will dig into the rest of list in the days to come.

But before I get to that, there is one question that looms up unavoidably about this thing: What should we call it?

It’s not an agreement, Senator Schumer’s aides are at pains to insist. “Leader Schumer never agreed to any of the conditions Sen. Manchin laid out; he merely acknowledged where Sen. Manchin was on the subject at the time," a Schumer spokesperson said to Burgess Everett, who unearthed the document in a report for Politico. Schumer’s office shared the same statement with Pawprints and refused to say anything else for the record. “Leader Schumer made clear,” the statement continues, “that he would work to convince Sen. Manchin to support a final reconciliation bill – as he has doing been for weeks.”

Judged by Schumer’s subsequent actions, this is hard to dispute. In all of August and September, Schumer pressed forward with a reconciliation bill two trillion dollars larger than the one called for in the document he signed.

But whoever wrote that document was trying to tell a somewhat different story. It’s styled as an “Agreement to Start Budget Resolution,” with signature lines at the bottom—a traditional indication of a binding agreement. Its only self-referential line reads: “Senator Manchin does not guarantee that he will vote for the final reconciliation legislation if it exceeds the conditions outlined in this agreement.” (emphasis added) While using the term agreement, of course, this line corroborates the view that the document is outlining Manchin’s position—even implying without stating that his support would be guaranteed if his “conditions” are met.

Schumer himself was clearly worried that his signature would be read to indicate a final acceptance of the terms. He scrawled beneath it a clarification: “I will try to dissuade JOE on many of these.”

Considering this evidence, it seems to me the document is best referred to as a proposed term sheet—the sort of piece one party puts together at the outset of a negotiation outlining the deal that they hope to make. Schumer’s decision to sign his name on a term sheet that he didn’t fully agree to—simply for the purpose of acknowledging it—is unorthodox. But we have plenty of indications that he meant nothing else by signing.

So what are the terms on this term sheet? Well, they’re pretty strange.

$1.5 Trillion

First, we have the topline number, which you’ve almost certainly heard about in the news: $1.5 trillion. Demanding that other Democrats drastically scale down their ambitions is standard Blue Dog fare, and Manchin often leads the pack, jumping into controversies early and vetoing progressives ideas. It’s one of the reasons his corporate backers prize him so highly.

“Joe Manchin, I talk to his office every week,” Exxon lobbyist Keith McCoy said in a secretly taped interview with a British news outlet earlier this year. “He’s sort of the kingmaker. And he’s not shy about staking his claim early and completely changing the debate.”

What’s odd is that Manchin chose a different strategy here. In the days before the July 28th term sheet, Democrats were seeking consensus on a larger topline number, $3.5 trillion, based on a compromise struck in the Senate Budget Committee. And Manchin was notably circumspect.

While Manchin put his own $1.5 trillion figure on paper in the term sheet with Senator Schumer, neither he nor Schumer made it public nor shared it widely. At the time, and for weeks afterward, Manchin was publicly cagey about his position, only expressing opposition to the larger $3.5 trillion package. Many Democrats would express surprise when his long-held topline number came to light two months later.

“It’s always helpful when you’re negotiating to have information about the other people you’re talking about,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren, the vice chair of the Senate Democrats’ conference, told the Huffington Post, adding she was “not pleasantly” surprised by the revelation. Other members of Democratic leadership, like Sen. Stabenow, also told the Huffington Post they had not been aware of the term sheet. The close hold of Manchin’s topline number helped to delay the negotiations now occurring over potential cuts.

Begin debate on Reconciliation bill No earlier than October 1, 2021

The second condition on Manchin’s term sheet, and one he felt strongly enough about to put in boldface type, is a demand that Congress not begin work on the reconciliation bill until the first day of October.

The crucial context for this line item is that the reconciliation bill is one track of the Democrats’ two track approach to infrastructure legislation. The second track is an infrastructure bill that enjoys substantial Republican support, as well as the enthusiastic support of Manchin, Sinema, and a group of Blue Dogs in the House; that bill passed the Senate in the summer. Pelosi and progressives always viewed the bipartisan infrastructure bill as their leverage to keep moderates on board and loudly committed not to pass it in the House until the Senate had also sent them a passed reconciliation bill.

After it passed, Manchin’s allies in the House went to work attacking this linkage. A group of Blue Dogs led by Rep. Josh Gottheimer pressed Speaker Pelosi to force a vote on the bipartisan infrastructure bill by late September. The kayfabe version of this deal at the time was that it gave Congress a short window to get the $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill together and pass it by late September too. “Progressives… said afterward that Pelosi had simply reiterated her earlier plans to attempt to pass both massive bills by the end of September,” a Politico story reported when an agreement on the late September date was reached.

Manchin’s private understanding with Schumer, however, was that floor debate on the reconciliation bill could not begin in Senate until after the planned vote on the bipartisan infrastructure bill in the House. This secretly made it impossible for the two track strategy to succeed on the progressives’ and Blue Dogs’ terms.

Funds in the new legislation cannot be disbursed until all funding from COVID legislation and ARP has been spent

This is where the character of the term sheet begins to stray from frustrating to just plain bizarre.

The third item on Manchin’s list is a demand, again in bold, that the reconciliation bill’s spending programs remain inactive until all the money from Congress’s Covid-19 relief packages, including the American Rescue Plan, is spent.

But the Covid relief legislation, on one hand, and the reconciliation bill, on the other, are addressed to almost entirely separate subjects. To take one example, the Covid laws include the money Congress has appropriated for rent relief during the pandemic. Those funds have been notoriously difficult to get out the door because the program depends on the fifty states to identify who is eligible and send the checks. Manchin’s stipulation would require all of that money to be allocated and spent by the states before a penny could be spent on the reconciliation bill’s Clean Electricity Performance Program, which would pay utilities to switch to sustainable forms of electricity generation.

Federal Reserve ends quantitative easing

Quantitative easing (QE) is a Federal Reserve initiative to buy long term securities from financial institutions on the open market. It’s considered an unconventional approach to monetary policy because the Fed usually limits its purchases to shorter term government securities.

The fourth and last boldface item on Manchin’s term sheet calls for the Fed to end the practice. It’s unclear what this means though, both to me and to the congressional staffers I asked. Is Manchin seeking an agreement from the current Fed Chairman to stop QE for now? Does he want Congress to make rules about its future use? Would he like to have the reconciliation bill outlaw the practice altogether?

The indeterminacy of this QE request makes it hard to discuss, and it highlights the oddity of Democrats’ current efforts to slash and hogtie their programs to fit into Manchin’s topline number. Even if they do all that, it seems to me, they’re still likely to have to contend with the other stipulations in the document, many of which are vague and poorly understood. If Manchin turns out to be seeking a strong restriction on the Fed’s toolbox—like banning a practice that proved essential in the Fed’s response to the financial crisis—these five words, as much as the topline, could put some votes that Democrats will need at risk.