Jack Smith Seeks a Gag Order for Donald Trump

A New Front Opens in Trump's January 6th Case

Friday afternoon brought the news that the Special Counsel team that has secured two federal indictments of Donald Trump had sharpened their confrontation with him by seeking to put his public statements under judicial supervision.

Earlier this month, it was revealed, the Special Counsel filed a motion that cites a litany of inflammatory statements Trump has made before and after his indictment and asks for a court order “imposing limited restrictions on certain extrajudicial public statements by the parties and attorneys in this case.”

A gag order is a very familiar, if not exceedingly common, judicial measure to restrain litigants’ attempts in civil and criminal matters to try their issues in on the public stage rather than in the courtroom, and a wealth of case law addresses the conflict between the court’s interest in protecting the integrity of its proceedings and the litigants’ rights to free expression. Nevertheless, this motion by the Special Counsel raises the prospect of a U.S. District Court overseeing the public engagement of an active presidential candidate and (almost inevitably) imposing sanctions against him when he oversteps the limitations of the court’s order, which is sure to give Judge Chutkan a degree of discomfort as she considers the future course of this case. The alternative of watching Trump’s inflammatory behavior escalate, threatening phone calls to chambers become more regular, and the judge’s control of the proceedings fade in the event of a denial must also make the court queasy. (The motion also seeks to regulate the Trump team’s engagement with any potential jurors.)

Because the motion included identifying information about potential witnesses and informants whom the Special Counsel contends Trump has targeted and whom his supporters have threatened, the prosecutors sought to file the motion with redactions of that identifying information.

Trump’s lawyers opposed the sealing request. After ten days of legal wrangling over the issue that was largely conducted outside the public eye, Judge Tanya Chutkan published an opinion and order agreeing to the government’s redactions and the text of the motion appeared on the public docket for the first time a short while later.

The motion’s extensive background section revealed how closely the prosecutors have been watching Trump’s online behavior in the weeks since his indictment in the January 6th case. “Since the indictment in this case, the defendant has spread disparaging and inflammatory public posts on Truth Social on a near-daily basis regarding the citizens of the District of Columbia, the Court, prosecutors, and prospective witnesses,” the prosecutors wrote. “Like his previous public disinformation campaign regarding the 2020 presidential election, the defendant’s recent extrajudicial statements are intended to undermine public confidence in an institution—the judicial system—and to undermine confidence in and intimidate individuals—the Court, the jury pool, witnesses, and prosecutors.”

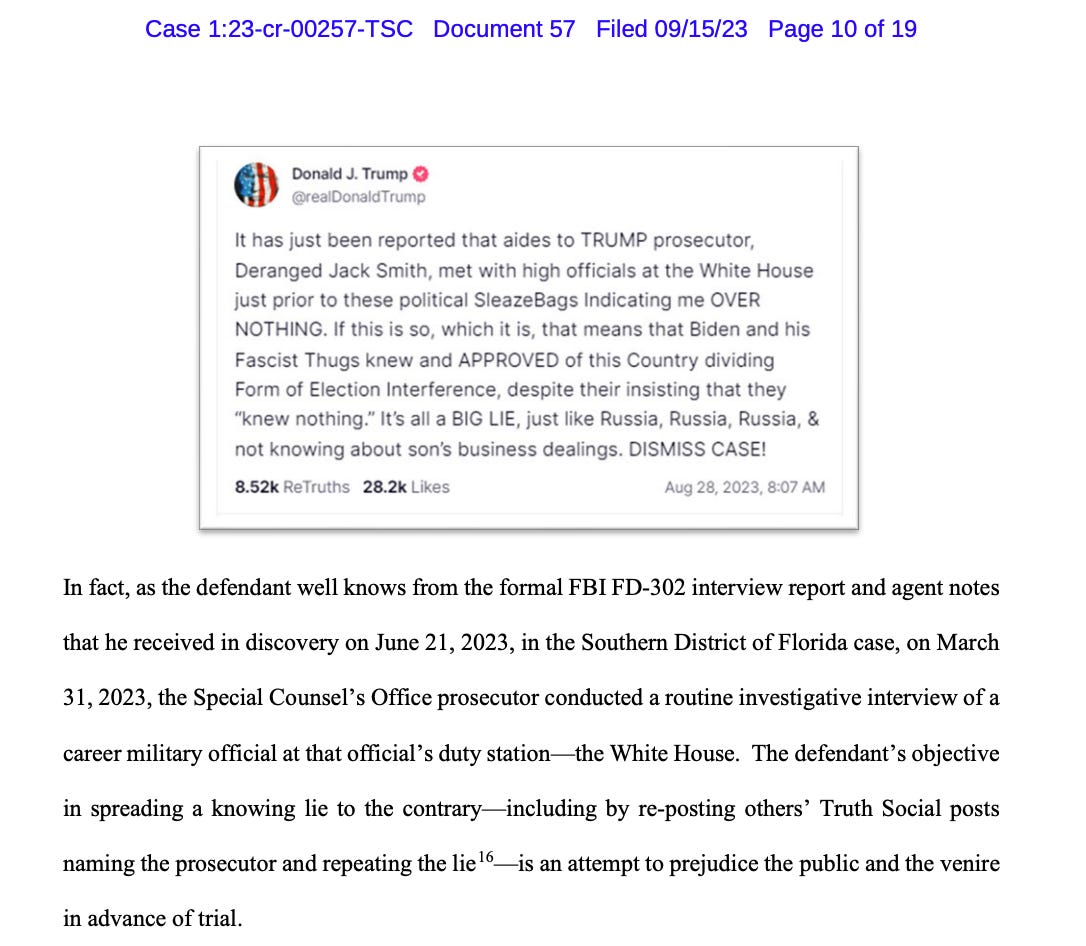

The prosecutors embedded ten of the former president’s posts on his vanity social media platform, Truth Social, to illustrate his inflammatory communications. They also took the opportunity to answer a few of Trump’s allegations about their conduct.

For example, in late August, citing a New York Post story, Trump posted that the Special Counsel’s team had taken a meeting with officials in the White House, concluding that they had been coordinating with Biden politically. The DOJ had given the Post a tight-lipped statement that the meeting had been a “case-related interview,” and a background source (almost certainly speaking for the DOJ as well) had told the newspaper that the interview was with a career staffer who’d also worked at the White House during the Trump administration.

In its motion, the Special Counsel team reveals that the interview was actually with a “career military official” posted to the White House—a fact it contends Trump knew from the discovery provided to him almost a month before his Truth Social post.

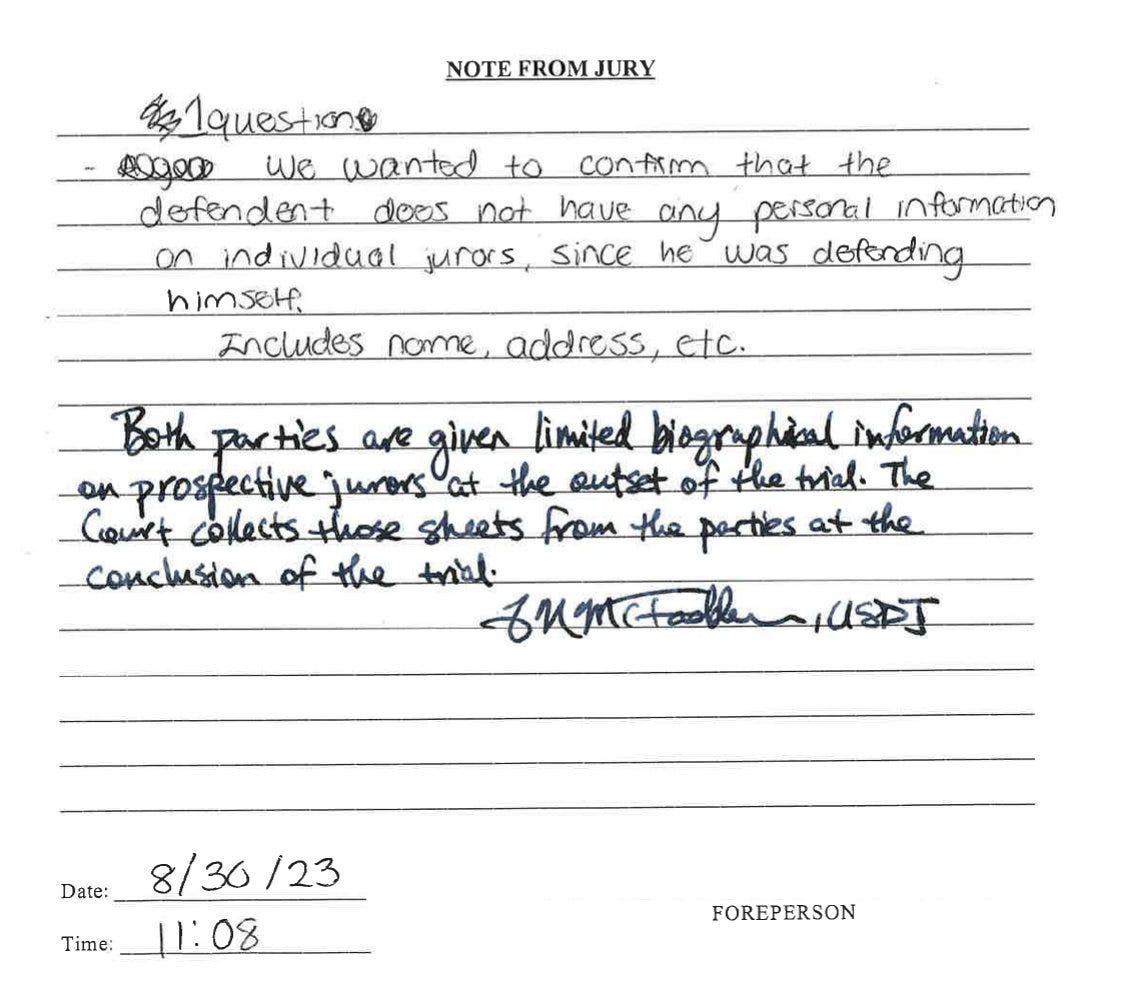

Arguing that Trump knows his inflammatory statements lead directly to harassment from his supporters, the Special Counsel’s team also invoked two recent stories to illustrate the threat to judges and jurors. The first story, arising from a criminal case in Texas, concerns a woman who called Judge Chutkan’s chambers to make a series of racist threats against Chutkan and Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee, both women of color. The caller threatened to “kill anyone who went after former President Trump.” (At a detention hearing, the woman’s father testified that every day she drinks “too many beers” while watching the news, and then “starts calling people and threatening them.” But, the father said, she “never leaves her residence and therefore would not act upon her threats.”) The second story comes out of a criminal trial for another January 6th defendant, Brandon Fellows, who had famously boasted “I have no regrets” in a round of media interviews after the sacking of the Capitol. During its deliberations, the clearly worried jurors sent a note to the judge asking if Fellows had access to their identifying information (“names, address, etc.”), given that he had acted as his own defense attorney in the case. The judge somewhat sheepishly wrote back that Fellows had been given “limited biographical information” about the jurors, but that the court had collected those papers back from him at the end of the trial.

The jury convicted Fellows anyway.

New subscriber. Looking forward to to your keen analysis here instead of Twitter. I have been an avid follower and I appreciate your perspective (and humor).